*UPDATE* Printable PDF Road Trip 1

With spring just a few weeks away it’s time to introduce a new blog feature, Road Trips! This is the first of what I hope will be many that will be cataloged by region in the Road Trips menu bar above.

With spring just a few weeks away it’s time to introduce a new blog feature, Road Trips! This is the first of what I hope will be many that will be cataloged by region in the Road Trips menu bar above.

If you have a request for a trip through a particular region, the Road Trips page is open for comments. Go ahead and leave a suggestion, and I’ll work one up.

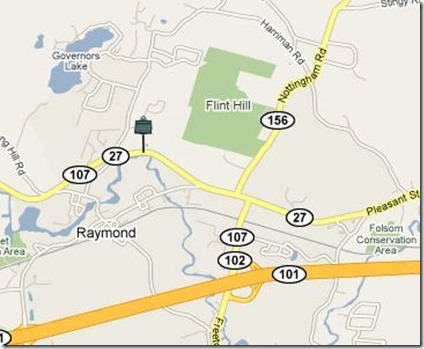

The Seacoast inside I95 is home to 14 markers (15 if we include the Weeks House just on the other side of the highway). Marker Icons on the maps have blog posts already, green placemarks do not. Blogged markers are linked as appropriate.

There are 2 clusters of markers inside I95; Portsmouth/Rye and Hampton/Seabrook.

This Road Trip will cover the northern markers through Portsmouth, down the coast, and finishing up at the North Hampton/Rye border on Rt 1. 9 markers with an optional 10th (Weeks House). Hampton and Seabrook will be the next road trip (and a shorter one, at that).

Part 1: Portsmouth.

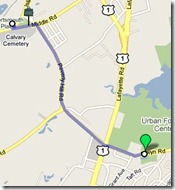

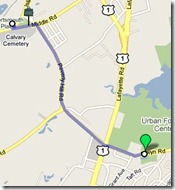

![75zpic1[1] 75zpic1[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/75zpic11.jpg?w=221&h=167) The first marker is #75 Portsmouth Plains . From I95 (north or south) get off at Exit 3, and take a right at the end of the ramp. The Marker is about a mile past the interstate on your left. From the south coast, get on Rt 1 north, and take a left at the lights after Lafayette Plaza Shopping Center onto Peverly Hill Rd, the left at the junction of Rt 33 (about a mile) the marker is just to your right. Not much to see here except a baseball field. It’s more a drive-by marker than a stop and visit marker. It was a different place 314 years ago.

The first marker is #75 Portsmouth Plains . From I95 (north or south) get off at Exit 3, and take a right at the end of the ramp. The Marker is about a mile past the interstate on your left. From the south coast, get on Rt 1 north, and take a left at the lights after Lafayette Plaza Shopping Center onto Peverly Hill Rd, the left at the junction of Rt 33 (about a mile) the marker is just to your right. Not much to see here except a baseball field. It’s more a drive-by marker than a stop and visit marker. It was a different place 314 years ago.

“In the pre-dawn hours of June 26, 1696, Indians attacked the settlement here. Fourteen persons were killed and others taken captive. Five houses and nine barns were burned. This plain was the Training Field and Muster Ground. Close by stood the famous Plains Tavern (1728-1914) with its Bowling Green where many distinguished visitors were entertained.”

From here take a right on Peverly Hill Rd just to the east, cross Rt 1 at the lights onto Elwyn Rd. Marker #127, John Langdon. It’s on the left about 1/4 mile past Rt 1.

From here take a right on Peverly Hill Rd just to the east, cross Rt 1 at the lights onto Elwyn Rd. Marker #127, John Langdon. It’s on the left about 1/4 mile past Rt 1.

Signatory to the Constitution, Governor, President of the U.S Senate among other amazing accomplishments. He was born on this farm in 1741. This marker is different from many others, the text continues on the reverse side. The house is open for tours from June through October, or you can rent the grounds for your next shindig.

Mr. Langdon will be covered in detail once we get to the Revolution.

Our next marker is #194 Wentworth- Coolidge Mansion. Continue east on Elwyn Rd. to the Rotary, then north on Sagamore Ave. The marker is a mile ahead, just past the intersection with Little Harbor Rd. Take a right on Little Harbor Rd and follow it to the end to get to the actual Mansion.

I hope you brought some snacks to munch along the way, as this is a beautiful spot on a nice day. The official State Park page is here. I’d recommend this spot for some great photo opportunities. Here are a few from a visit last fall.

When you’re finished taking in the view, hop back in the car and head back out to Sagamore Ave.

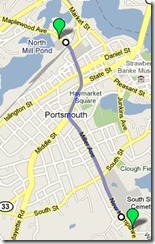

This next marker is optional. If you don’t mind navigating across downtown, then backtracking through the city again, head for marker #114 North Cemetery. It’s from 1753, and has many famous New Hampshire residents buried there. Skip ahead if you’re eager to get to the coast markers.

It’s about a mile to the Cemetery. Once back at Sagamore Ave (Rt. 1A), take a right and follow 1A. Sagamore turns into Miller Ave, and ends at the lights at Middle St, Rt. 1. Turn right onto Middle St and stay on Middle. Cross State St. and Islington St., you’re on Maplewood Ave. The cemetery and marker are 1/4 mile ahead on your left, across from the old Portsmouth Herald building.

“The Town of Portsmouth purchased this land in 1753 for 150 pounds from Col. John Hart, commander of the N.H. Regiment at Louisburg. General William Whipple, Signer of the Declaration of Independence, Gov. John Langdon, Signer of the Constitution, Capt. Thomas Thompson, of the Continental Ship Raleigh, are among noted citizens buried here.”

John Langdon, you may remember, we met a few markers ago. Did you know Portsmouth has a committee to preserve old graves? Wander down to the right end of the cemetery, and you’ll find the “Old Union” section with a plaque describing some of the people buried there. After getting your fill here, it’s time to meet up with the folks that skipped this marker for the coast ride.

From the cemetery, turn back around the way you came and head back to State St, and turn left. At the 2nd light, turn right onto Pleasant St, which turns into Rt 1B.

Part 2: The Coast.

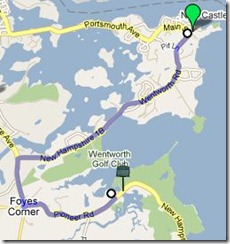

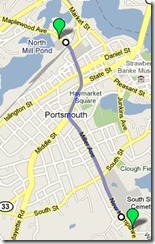

If you are skipping the marker #114, take a right on Sagamore Ave., and at the light at the end of the cemetery, turn right onto South St. You’re looking for Newcastle road on the right (less than 1/2 mile), turn right. When the road ends,turn right on 1B. We’re all one big happy group again.

Don’t rush as you follow 1B to center Newcastle. There are some nice views across the bay on this stretch, and some cute back roads overlooking the bay (with nice homes) once you get near Newcastle. At the very top of Newcastle turn left onto Wentworth Rd., and the Portsmouth Coast Guard station, marker #4 William and Mary Raids is just on your right with a little parking and picnic area.

If you have the time visit the old fort now known as Fort Constitution. There is parking outside the gate of the station, and they don’t mind you visiting. Just stay on the blue line! The fort itself has placards describing what went on there, and what you’re seeing. Oh, and there’s a light house to photograph as well, if you can find the right vantage point. This is yet another un blogged marker, but we’re getting close.

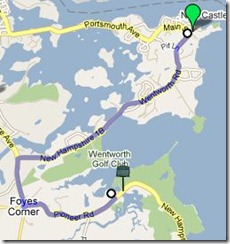

The next marker is only a few miles away, #72 Odiorne’s Point. As you leave the coast guard station, continue along Rt. 1B (Wentworth Rd), and when it ends, turn left on Sagamore Ave. At the rotary, go left on Rt 1A. The marker is located on the left, just across the bridge before the entrance to the Odiorne Point boat launch.

The next marker is only a few miles away, #72 Odiorne’s Point. As you leave the coast guard station, continue along Rt. 1B (Wentworth Rd), and when it ends, turn left on Sagamore Ave. At the rotary, go left on Rt 1A. The marker is located on the left, just across the bridge before the entrance to the Odiorne Point boat launch.

The site of the first settlement in New Hampshire by David Thompson now hosts a very nice State Park. There are plenty of walking paths to be explored, remains of some of the original settlement foundations, and the Seacoast Science Center to visit. The main entrance is down the road from the marker on the left. Check the State Park web site (link above) for opening dates and such.

When ready, continue down Rt 1A to the next mark … err … post sticking out of the ground. Yes, it’s the infamous marker #18 Isles of Shoals. As you drive down 1A, the post is on the left at a small parking area, just after Fairhill Ave. The marker was vandalized, removed and never replaced. It read:

About six miles directly out to sea, this cluster of islands abounds in legend and history. Before 1614, when the famous Captain John Smith mapped the rocky and surf-lashed Isles, early fishermen, traders and explorers had a part in their history.

![18web11[1] 18web11[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/18web111_thumb.jpg?w=349&h=263)

A clear day will offer a great view of the islands in the distance. If you’re trying to take pictures a telephoto lens is probably a good idea.

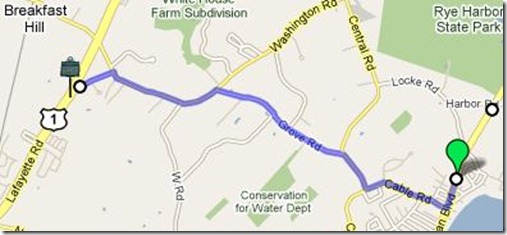

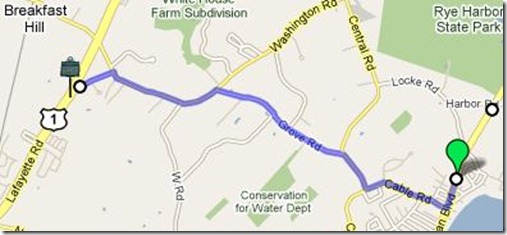

The next marker is down the road a bit, almost exactly 3 miles, so set your odometer. No map for this one! Take it slow and enjoy the views as you pass Wallis Sands State Beach, Rye Harbor State Park and then turn inland for a bit. Once inland, on the left after Locke Rd., Marker #63 Atlantic Cable Station and Sunken Forest is hiding at the edge of the marsh.

The receiving station for the first Atlantic Cable, laid in 1874, is located on Old Beach Road opposite this location. The remains of the Sunken Forest (remnants of the Ice Age) may be seen at low tide. Intermingled with these gnarled stumps is the original Atlantic Cable.

Fun fact: I received an email from a reader pointing out that this is not, in fact, the first Atlantic Cable station (Backed up with facts). I look forward to researching this marker in the future. And now it’s on to the final marker for this road trip.

About .2 miles south of the last Marker, turn right on Cable Rd., then right, onto Central Rd. Next, turn left onto Grove Rd. which ends at Washington Rd. A left onto Washington. Your 5th left is Dow Lane, turn down there it ends at Rt 1. The marker is actually just a bit south on Rt 1at the Rye/North Hampton town line.

![62zpic1[1] 62zpic1[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/62zpic11_thumb.jpg?w=456&h=343)

And so we come full circle. Marker #62 Breakfast Hill. The companion marker to the first marker from this trip, Portsmouth Plains.

On the hillside to be seen to the north of this location a band of marauding Indians and their captives were found eating their breakfast on June 26, 1696, following the attack at the Portsmouth Plains. When confronted by the militia the Indians made a hasty exit leaving the prisoners and plunder. This locality still enjoys the name of Breakfast Hill.

Postscript:

Whew, this was a lot longer than intended and covered a lot of ground. It looked good mapping it all out. The distances between markers is pretty short, but explaining it all seems wordy.

I’d like to ask regular readers what you think. Are these worthwhile? To many markers? Need something short to print? Any and all comments welcome.

Be well!

Mike

42.764811

-71.439788

.png)

![75zpic1[1] 75zpic1[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/75zpic11.jpg?w=221&h=167)

![18web11[1] 18web11[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/18web111_thumb.jpg?w=349&h=263)

![62zpic1[1] 62zpic1[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/62zpic11_thumb.jpg?w=456&h=343)

![Town-Seal-RGB[1] Town-Seal-RGB[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/02/townsealrgb1.jpg?w=91&h=91)

![51866W6EBYL._SL500_AA240_[1] 51866W6EBYL._SL500_AA240_[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/02/51866w6ebyl-_sl500_aa240_1.jpg?w=104&h=104)