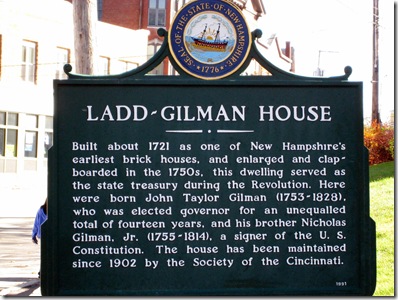

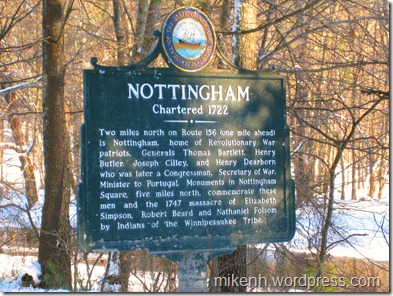

Marker Text:

Two miles north on Route 156 (one mile ahead) is Nottingham, home of Revolutionary War Patriots, Generals Thomas Bartlett, Henry Butler, Joseph Cilley, and Henry Dearborn who was later a Congressman, Secretary of War, and Minister to Portugal. Monuments in Nottingham Square, five miles north, commemorate these men and the 1747 massacre of Elizabeth Simpson, Robert Beard and Nathaniel Folson by Indians of the Winnipesaukee Tribe.

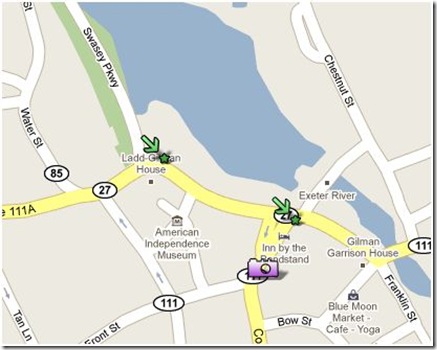

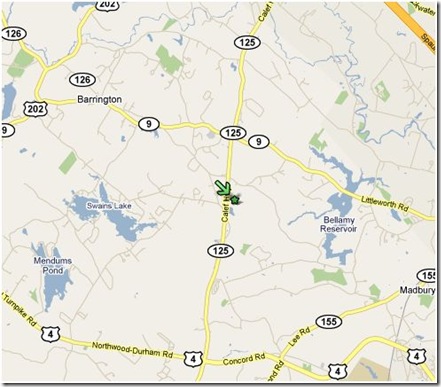

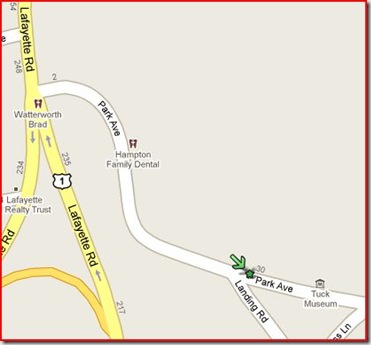

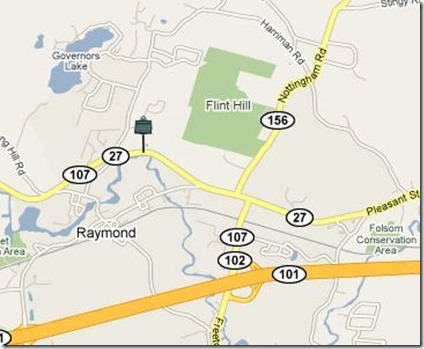

This marker is located on Rt 27/107 in Raymond, about 3/4mi west of the junction of Rt 156. Nottingham Square is 5 miles north on Rt 156.

Land grants were coming fast and furious in the 1700s. Massachusetts had pretty standard language for all of them, and reading this stuff can put you to sleep quick. I hope that’s not the case here as we see how a town on the edge of the frontier came to be.

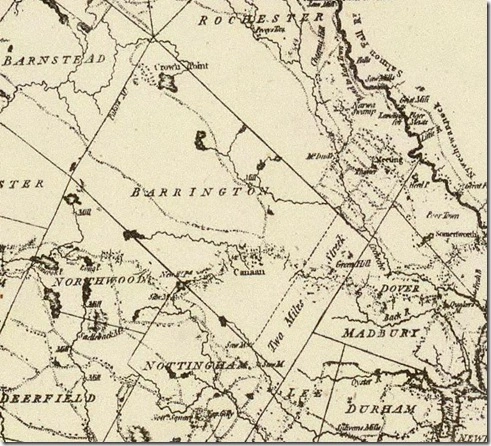

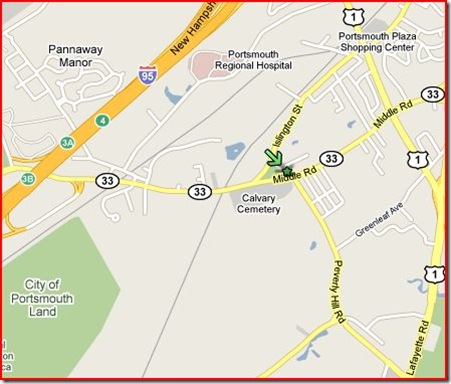

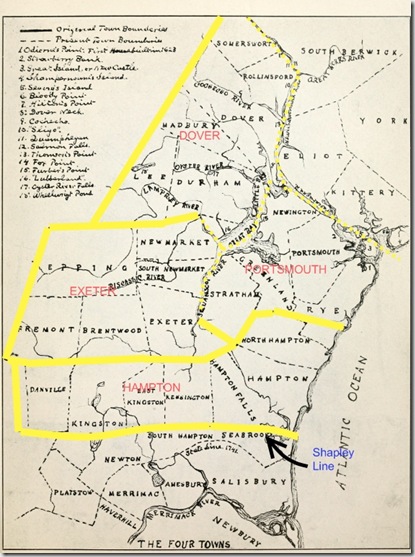

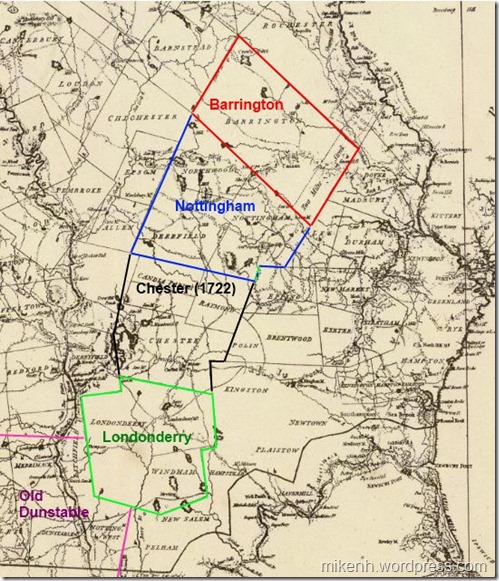

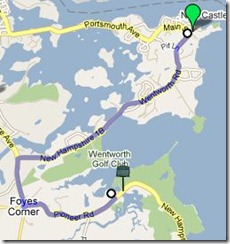

The Nottingham land grant is the next in the expansion of New Hampshire, extending a protective ring westward from the coast. Old Dunstable-1673, the Scotch-Irish settlement (Londonderry)-1719, and The Two Mile Streak-1719 in Barrington were all being populated around this time. When Nottingham is added (containing today’s towns of Nottingham, Deerfield and Northwood) there is an effective wall set up to help guard against Indian attacks and expand the wealth of New Hampshire. A map might help here.

The grants of the early 1720s.

The grants of the early 1720s.

The request for a land charter was submitted without a suggested name to Boston on April 19, 1721 and signed by 101 men. Boston responded on April 28th:

We, the dwellers at Boston, being in number a considerable part of the persons entered in a petition late granted by the authority of New Hampshire, April 21,1721, for settling a town norwestward of Exeter, etc., at a meeting among ourselves duly warned,

It is voted, That the tract of land contained and set forth in the said petition shall be called New Boston, if our brethren at Newbury and elsewhere are of the same mind, and the gentlemen of the province of New Hampshire approve of ye same to whom we submit the matter.

The people named in the charter were of many different backgrounds and motives. Most of them came from coastal areas from Portsmouth to Boston. Land speculators were involved, as were entrepreneurs trying to expand their wealth. Many were veterans of various Indian wars – or their heirs - granted land as payment for service to the colonies. 20 New Hampshire men were added to the charter in December 1721 by the folks in Exeter who were responsible for it’s execution.

But all of them – regardless of station or wealth – were required meet the terms of the grant. The Royal Charter from George I, dated May 10, 1722 lays out all the details of elections and such. Each “Proprietor” was required to build a house and plow up and fence in at least 3 acres of land within 3 years, and plant the fields in the 4th year. Oh, and the charter changed the name to Nottingham.

But all of them – regardless of station or wealth – were required meet the terms of the grant. The Royal Charter from George I, dated May 10, 1722 lays out all the details of elections and such. Each “Proprietor” was required to build a house and plow up and fence in at least 3 acres of land within 3 years, and plant the fields in the 4th year. Oh, and the charter changed the name to Nottingham.

Land was set aside for the Proprietors to build a town Meeting House, school and parsonage within 4 years. They were also required to pay for any protection that may be needed and a town minister.

Charter in hand, the Proprietors went about the business of building a town. Planning meetings were held in Portsmouth or Exeter. At the first meeting in Exeter in June it was decided that “Major John Gilman, Capt. John Gilman and Capt. John Wadleigh be a committee to agree with men to build a bridge and make good ways to Nottingham.” As noted in a previous post, the Gilman family were quite influential in early Exeter.

There were no roads. The bridge in question was over the Lamprey River to facilitate connecting the town to Exeter. It took 2 years to build a way in, survey the land and finally get to the point where they could parcel out land.

The description of the chosen town center from 1724 is told to us thusly:

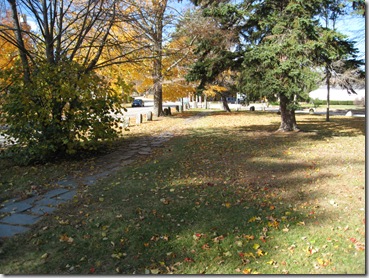

“But the position chosen for the compact part of the town was "beautiful for situation." It was upon the height of a large swell of land, gently sloping in every direction. It was twenty-five miles south-east from what is now the state capital, fourteen miles north-west from Exeter, and twenty west from Portsmouth. The blue waters of the Atlantic, and the white canvas of vessels entering the harbor at Portsmouth, could be distinctly seen; while little lakes sparkled like gems in the wilderness, and Pawtuckaway Mountain gracefully rose in the west, and Saddleback in a more northerly direction, and babbling streams, affording ample water-power, found their way along the valleys. Here, at an elevation of about four hundred and fifty feet above the sea level, they laid out a compact village with great exactness in the form of a cross.“

“But the position chosen for the compact part of the town was "beautiful for situation." It was upon the height of a large swell of land, gently sloping in every direction. It was twenty-five miles south-east from what is now the state capital, fourteen miles north-west from Exeter, and twenty west from Portsmouth. The blue waters of the Atlantic, and the white canvas of vessels entering the harbor at Portsmouth, could be distinctly seen; while little lakes sparkled like gems in the wilderness, and Pawtuckaway Mountain gracefully rose in the west, and Saddleback in a more northerly direction, and babbling streams, affording ample water-power, found their way along the valleys. Here, at an elevation of about four hundred and fifty feet above the sea level, they laid out a compact village with great exactness in the form of a cross.“

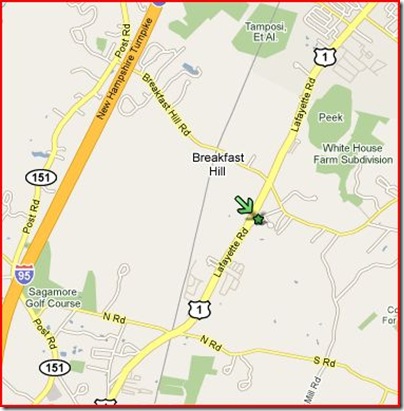

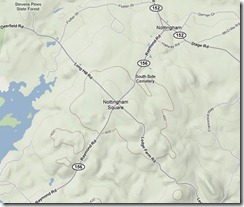

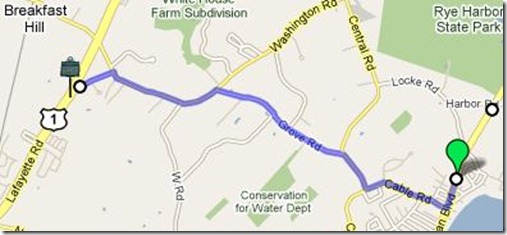

The small map above (click for big) shows Nottingham Square today, with the originally laid out roads in the form of a cross. The four streets were originally named King St (Southeast to Exeter and the Lamprey bridge), Fish St. (Southwest to “Tuckaway” pond), Bow St (Northwest to Bow pond), and North St. (Northeast toward North River). Roads are said to have been built “Four Rods wide” – about 64 feet!

Parcels of land at the center were assigned to the meeting house, schools, and of course, special plots for the Governor and Lt. Governor. A total of 134 plots were parceled and lots drawn for ownership. Generally, the further from town, the more acreage.

The first meeting held in Nottingham itself occurred in 1727 in the town “Block House” – or meeting house. By then the roads had been laid, town center built and folks were beginning to work the land. The first order of business was to raise funds to build a mill on the “Tuckaway” river to process lumber.

Like many of the settlements around this time lumber, charcoal and Ships Masts (required by law to be sent to England for the Navy) were the main sources of income. Farming was of less value because of our rocky soil, but it was good land for raising livestock and planting crops for a family’s use.

.png) Over the next 60 years as Nottingham grew, people in the farther reaches of the town were complaining that it was to far to the town center. The original planners misjudged the actual size of the grant and positioned the town center in the southeast corner of the grant. Deerfield would later be set off as it’s own town in 1766, and the folks who lived in what they then called the “North Woods” would split again in 1773 to become Northwood.

Over the next 60 years as Nottingham grew, people in the farther reaches of the town were complaining that it was to far to the town center. The original planners misjudged the actual size of the grant and positioned the town center in the southeast corner of the grant. Deerfield would later be set off as it’s own town in 1766, and the folks who lived in what they then called the “North Woods” would split again in 1773 to become Northwood.

It’s hard to imagine the New Hampshire of the 1720s-1730s. Mr. Elliott Colby Cogswell History of Nottingham, Deerfield, and Northwood 1878 gives a glimpse into the early pioneer spirit.

"VARIOUS motives prompted men to engage in the settlement of some of our towns. Some were actuated by a spirit of enterprise. They delighted in seeing highways cut through the wilderness, smoke ascending from many a hill-top, — sign that the woodman’s ax was effecting clearings and rude dwellings were being constructed for those who were willing to dare and endure. It was for the greater safety of the lower towns to have the frontiers extended further from the coast-line, and the towns that were the centers of trade and influence encouraged every attempt to effect a new settlement.”

"VARIOUS motives prompted men to engage in the settlement of some of our towns. Some were actuated by a spirit of enterprise. They delighted in seeing highways cut through the wilderness, smoke ascending from many a hill-top, — sign that the woodman’s ax was effecting clearings and rude dwellings were being constructed for those who were willing to dare and endure. It was for the greater safety of the lower towns to have the frontiers extended further from the coast-line, and the towns that were the centers of trade and influence encouraged every attempt to effect a new settlement.”

Postscript:

Mr. Cogswell’s book, celebrating the Northwood centennial was the only source used for this post. The proceedings of the event are covered, including poetry, song, speeches, etc. I didn’t read all the speeches (they sure could speechify back then) but enjoyed “The Old Elm Tree” by S. Clarke Buzell was my favorite of those I did. Check it out if you have a moment extra.

![75zpic1[1] 75zpic1[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/75zpic11.jpg?w=221&h=167)

![18web11[1] 18web11[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/18web111_thumb.jpg?w=349&h=263)

![62zpic1[1] 62zpic1[1]](https://mikenh.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/62zpic11_thumb.jpg?w=456&h=343)