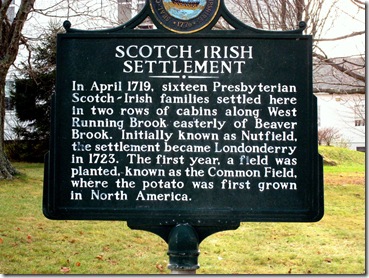

Marker Text:

In April 1719, sixteen Presbyterian Scotch-Irish families settled here in two rows of cabins along West Running Brook easterly of Beaver Brook. Initially known as Nutfield, the settlement became Londonderry in 1723. The first year, a field was planted, known as the Common Field, where the potato was first grown in North America.

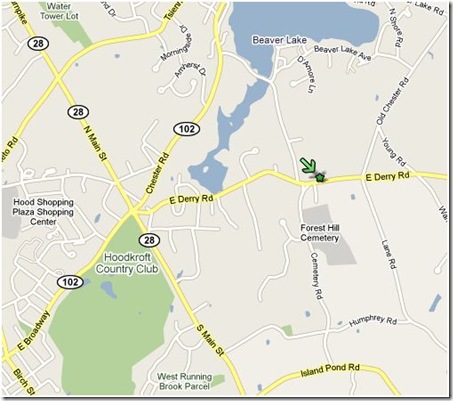

Located about a mile east of the Derry rotary on East Derry Rd in front of the East Derry Church and site of the first meetinghouse. Marker erected in 1969.

The Scotch-Irish – also known as the Ulster-Scots – have a pretty interesting history. Back in the days of King James I and through the 1600s, there were settlers sent from Scotland to Catholic Ireland. One of the first was in what came to be known as Ulster County. The major town was … Londonderry!

Of course the native Catholics weren’t to happy about having land given to these immigrating Presbyterian Scotsmen. It didn’t take long before hostilities broke out.

By 1641 The Irish Rebellion was in full swing. This was pretty much the start of the centuries long strife between the Protestants and Catholics in Ireland. We don’t need to go through it all here. Lets just follow the Scotch-Irish that came to New Hampshire.

As previously noted, the Scotch-Irish were Presbyterians. They had splintered away from the official English church. In 1688 the ascension of William to the English throne brought relative peace to Ireland. The Scotch-Irish were allowed to practice their religion, but were required to pay the church of England 10% of everything they produced. They land they lived on and worked was only leased to them by the crown – they could be evicted at any time.

Edward Parker, in his 1851 “History of Londonderry” quotes an earlier historian commenting on the feelings in Northern Ireland at the time between the Protestants and the Catholics:

"On the same soil dwelt two populations, locally intermixed, morally and politically sundered. The difference of religion was by no means the only difference, and was perhaps not even the chief difference, which existed between them. They sprang from different stocks. They spoke different languages. They had different national characters, as strongly opposed as any two national characters in Europe. They were in widely different stages of civilization. There could, therefore, be little sympathy between them ; and centuries of calamities and wrongs had generated a strong antipathy. The relation in which the minority stood to the majority, resembled the relation in which the followers of William the Conqueror stood to the Saxon churls, or the relation in which the followers of Cortez stood to the Indians of Mexico."

So there they were. No real land ownership, taxed to support a church they didn’t believe in and surrounded by animosity from both the Irish Catholics and church of England. And they had heard things. Good things about new freedoms across the Atlantic. It didn’t take long for them to realize leaving for the new world might not be such a bad idea.

Four Presbyterian clergymen gathered all the interested families from their churches. 217 signed the request that was sent to Boston in the hands of Reverend Boyd. The colony said “sure, come on over!” and they did. They arrived in Boston in August of 1718.

In the fall of that year a gentleman named MacGregor took 16 of these families to Casco Bay to find a place to settle, but arrived late in the fall. They spent a miserable winter aboard ship, sick and hungry, iced into the bay. Boston sent enough food to see them to the spring.

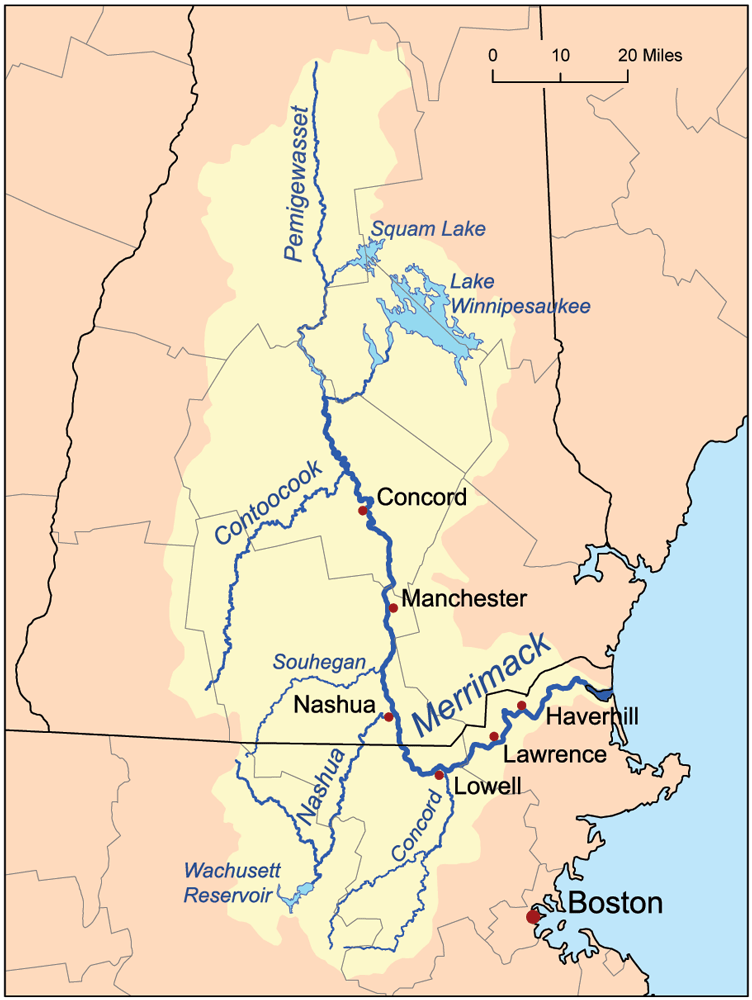

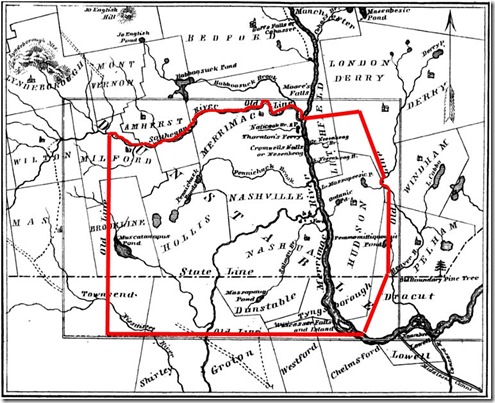

In the spring they explored the lands around Casco Bay but couldn’t find anything to their liking. So they struck west into the Merrimack valley, arriving at the settlement in Haverhill, MA. Once there they began asking about land that could be settled and were told of an area called Nutfield, about 15 miles northwest. The men went to explore the new area and fell in love.

They communicated the selection of the land to Boston – making their claim – and proceeded to build some crude huts before returning to gather up their families and few possessions for the trip to their new home. As the marker notes, 5 years later they renamed the town after their old home in Ireland, Londonderry.

Now to important stuff. Potatoes! That’s quite a claim on the marker: “The first year, a field was planted, known as the Common Field, where the potato was first grown in North America.” Could it be true? This calls for some intense googling.

Now to important stuff. Potatoes! That’s quite a claim on the marker: “The first year, a field was planted, known as the Common Field, where the potato was first grown in North America.” Could it be true? This calls for some intense googling.

It seems that a few people brought some potatoes in the 1600s, but no one really established a potato plantation. All of the most reliable Potato Historians do indeed place the first legitimate Potato farms in Londonderry, 1719. Take that Maine!

Special bonus for all my Crafty readers, the Official State of New Hampshire Tartan!

Yes we do have one, approved by the state legislature in 1995 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the New Hampshire Highland Games.

Here is the Sett for the Tartan:

green 56, black 2, green 2, black 12, white 2, black 12, purple 2, black 2, purple 8, red 6, purple 28

Green represents our forests, Black the granite of our mountains, White is the snow, Purple our state flower the Lilac and bird the purple finch. Red represents all our state Heroes.

I’ll let some of our weavers explain how a list of colored string gets turned into tartan. Looms scare me.

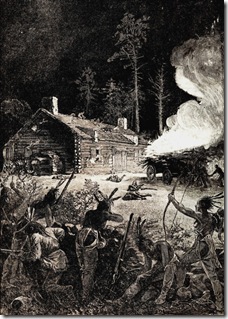

vulnerable to attack on the frontier.

vulnerable to attack on the frontier.

keep up or die. They travelled for 15 days all told, and as was the custom of the Indians at the time the captives were split between the participating Tribes.

keep up or die. They travelled for 15 days all told, and as was the custom of the Indians at the time the captives were split between the participating Tribes.