Marker Text:

Was fought between 1722 and 1725 against several tribes of eastern Indians. The principal campaigns took place in the Ossipee region and led to the eventual withdrawal of the Indians to the north. Commemorated in Colonial literature by "The Ballad of Lovewell’s Fight."

I was unable to locate this marker, erected in 1965, on a trip up Rt. 16. It’s possible it was hidden behind plowed snow. The map below represents a “best estimate” of the location. The NH state description reads “Located in a grassy plot about 2.5 miles north of Center Ossipee on NH 16 and 25, just north of the point where NH 16 combines with NH 25.”

As we have seen from the previous marker, Nottingham, the westward expansion of New Hampshire away from the seacoast began in earnest in the 1720s. The same thing was occurring next door in Maine as English settlements were being established along the Kennebec River deeper into the frontier.

There were two groups of folks that weren’t too happy about all this. The Indians, and the French. But mostly the French. They considered most of Maine their property and, following their tried and true tactics, goaded the local Abenaki Indians into the usual raids on frontier settlements. For many years the French were operating out of Montreal and today’s Canadian Provinces with access to the Atlantic. They also brought with them Jesuit Missionaries. These missionaries went out into the frontiers and established small churches among the Indians, teaching them and converting many to Catholicism. I bet you know what’s coming next.

France and England were in an uneasy peace for now, but the recent history of religious arguments and the English Civil War (posted about here and here) left the two countries polarized. And that spilled over to New England. The French, knowing the Indians were a superstitious people, convinced the Abenaki that the English were not interested in teaching them about God, and it was a sin to take their land (which of course the French were doing as well, but … Squirrel! They didn’t want them noticing that.)

France and England were in an uneasy peace for now, but the recent history of religious arguments and the English Civil War (posted about here and here) left the two countries polarized. And that spilled over to New England. The French, knowing the Indians were a superstitious people, convinced the Abenaki that the English were not interested in teaching them about God, and it was a sin to take their land (which of course the French were doing as well, but … Squirrel! They didn’t want them noticing that.)

So the Indians, prodded by the French burned down farms, killed livestock, and generally made life hell on the frontier. The English responded in the usual manner establishing Garrisons and Forts, and sending out hunting parties to track down the perpetrators. By 1721 things had really gone downhill, and at a meeting on Arrowsic Island ME., three Jesuits accompanied by Indians delivered a letter from the various tribes to the English giving them 3 weeks to get out of Maine or they would Murder them all and burn down their settlements.

The English were having none of that. One of the Jesuits, Sebastian Ralle was a particular troublemaker that had his little enclave near today’s Norridgewock ME. That winter a party of men was sent to capture him, but he escaped in to the woods. They took his strongbox which contained incriminating letters to and from the French Governor in Montreal, detailing the efforts to turn the Indians against the English. It was time for war!

The English were having none of that. One of the Jesuits, Sebastian Ralle was a particular troublemaker that had his little enclave near today’s Norridgewock ME. That winter a party of men was sent to capture him, but he escaped in to the woods. They took his strongbox which contained incriminating letters to and from the French Governor in Montreal, detailing the efforts to turn the Indians against the English. It was time for war!

The 4th French and Indian War was known by various names and lasted from 1721to1725. The most common was “Dummer’s War” and it’s also referred to occasionally as “Captain Lovewell’s War” which brings us to our marker.

ONE of the few incidents of Indian warfare naturally susceptible of the moonlight of romance was that expedition undertaken for the defence of the frontiers in the year 1725, which resulted in the well-remembered "Lovell’s Fight."

ONE of the few incidents of Indian warfare naturally susceptible of the moonlight of romance was that expedition undertaken for the defence of the frontiers in the year 1725, which resulted in the well-remembered "Lovell’s Fight."

Nathaniel Hawthorne, in his introduction to Roger Malvin’s Burial, from the collection of short stories “Mosses from an old Manse” 1854. Hawthorne writes a story about two wounded survivors of Lovewell’s final battle.

The heroics and story of Lovewell and his final battle were told throughout New England, and he and his men became early American Hero’s for their deeds. The centuries have dimmed the memories and stories, but they are still there to be found.

Lovewell commanded a group of militia from Old Dunstable (probably from what is today’s Nashua) known as “The Snowshoe Men.” Originally tasked with protecting the town, they were recruited to run scouting missions up the Merrimack river and into the Lake Winnepesauke area. They became so good at tracking and killing Indian raiders his contingent of men was increased to 70.

In the Winter of 1725 Lovewell set out on another campaign north toward Winnepesauke. When they arrived and scouted the usual Indian campsites they found that none had returned to the area. He sent back 30 men, and led the rest east toward the Piscataqua and the lakes near today’s Wakefield. The Indian raiders from the north frequently came by this area on their way to the coastal settlements.

In the Winter of 1725 Lovewell set out on another campaign north toward Winnepesauke. When they arrived and scouted the usual Indian campsites they found that none had returned to the area. He sent back 30 men, and led the rest east toward the Piscataqua and the lakes near today’s Wakefield. The Indian raiders from the north frequently came by this area on their way to the coastal settlements.

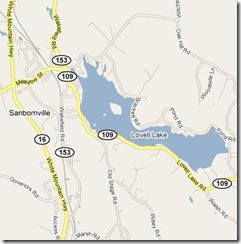

On February 20th, just before sunset they spotted smoke from a campfire along the shore of a lake. Lovewell hid until midnight, and quietly advanced on what was a fully equipped raiding party bound for Dover. They made short work of the sleeping Indians. Today, “Lovell Lake” in Wakefield (above) honors the Captain for his deeds.

The men then travelled south to Dover and Boston – scalps in hand – to collect the £100 per scalp bounty, and to resupply for their next mission. In mid march they set out for a known hostile Indian village even further north named Pequacket.

46 men left Boston including a Chaplain and surgeon. By the time they arrived at Ossipee Lake, 2 men had been forced to turn back, others were sick. They stopped on the west side of the lake to construct a small fort. Partially, it was in case they needed a place to retreat to from battle (there were no settlements this far north) and also as a place to leave the sick. 10 men remained behind at the fort, and 34 men resumed their march north in early May.

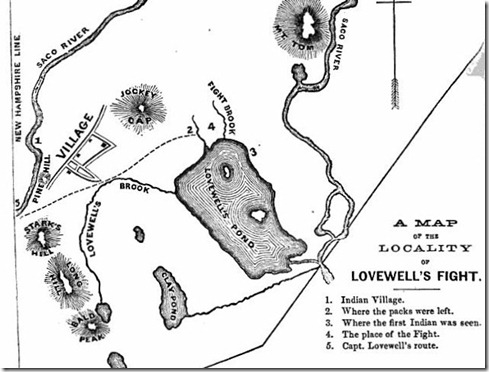

On the morning of May 8th, while encamped by a pond, Lovewell’s party heard the firing of a gun and saw a lone Indian across the pond. After discussing strategy the men assembled and circled the lake. They dropped their packs for easier movement and fighting, then followed and killed the lone Indian.

They returned to the place they dropped their packs, only to find them gone. The Indians had taken them. Paugus, the Indian chief had been following the English tracks. He determined that his tribe greatly outnumbered Lovewell and intended to fight. About 10am, while Lovewell’s party was searching for their packs, Paugus attacked.

Almost as soon as the intense fighting began Lovewell was shot and killed along with 8 other men. Paugus took casualties as well, but the English were seriously outnumbered. Paugus moved in to try and surround them and force surrender or kill them all. Lieutenant Wyman took over, and rallied the men to keep up the fight, having herded the men into a defensible position among rocks and logs with water offering protection from complete encirclement.

The fight raged on all day and to sunset. Lovewell’s men made a mighty stand and continued to thin the ranks of Indians. At nightfall the Indians retreated into the safety of the woods. Wyman waited until the moon rose and around midnight, began a retreat to the fort at Ossipee.

The retreat was initially 21 men, many mortally wounded. Some would never reach the fort at Ossipee. 2 men were too wounded to retreat and were left at the battle site alive with freshly loaded weapons. Of the 21, 5 would die before reaching a settlement due to lack of provisions or medical help. Those that did reach the fort found it abandoned. Some say as soon as the fighting started one man fled the field to warn the fort, and they all ran off. So the survivors had no packs, no food, no supplies and a long way to go. More than 50 miles to travel to the nearest settlements.

It’s hard to determine the actual number of Indians involved in the fight, but many put it around 80 (not just our poet friend above). When a party returned to the site of the battle they found and buried Lovewell and his men, and found Indian graves, one of which contained the body of Paugus.

THE BATTLE OF LOVELL’S POND

THE BATTLE OF LOVELL’S POND

Henry Wadsworth-Longfellow

Cold, cold is the north wind and rude is the blast

That sweeps like a hurricane loudly and fast,

As it moans through the tall waving pines lone and drear,

Sighs a requiem sad o’er the warrior’s bier.

The war-whoop is still, and the savage’s yell

Has sunk into silence along the wild dell;

The din of the battle, the tumult, is o’er,

And the war-clarion’s voice is now heard no more.

The warriors that fought for their country, and bled,

Have sunk to their rest; the damp earth is their bed;

No stone tells the place where their ashes repose,

Nor points out the spot from the graves of their foes.

They died in their glory, surrounded by fame,

And Victory’s loud trump their death did proclaim;

They are dead; but they live in each Patriot’s breast,

And their names are engraven on honor’s bright crest.

“These verses were written by Longfellow in his fourteenth year, and have interest as the first of his writing to appear in print. They were published in the Portland Gazette November 17, 1820.”

The Indians would abandon Pequacket village after the battle and head north to Canada. Today we know the place of this battle as Fryeburg, ME. The Pond where the battle occurred is named Lovewell’s Pond.

The survivors and the families of the dead would be greatly rewarded for their actions. The next marker will touch on that a bit.

Postscript:

Besides the books and sources linked in the post and the usual references linked in the sidebar, I used a few other on-line resources as well.

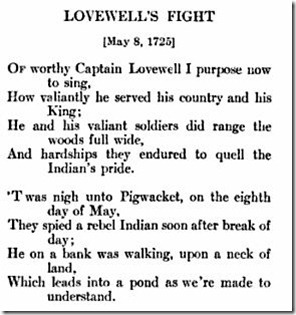

- An Interesting book first published in 1725 “The original account of Capt. John Lovewell’s "great fight" with the Indians” has all the names of the men involved and was the source of the map.

- The Hawthorne and Longfellow story and poem are appropriately linked to the original works.

- The excerpted poem screenshots are from an unknown author, and are snips of a much longer “Ballad of Lovewell’s Fight”. It’s in the volume “Poems of American History” written in 1922.

- There is another poem “Lovewell’s Fight” by Thomas Upham that can be found in a collection published in 1822.

One of the inspirations for the fight was a slaughter in NH of Thomas Lund and his band.

http://imaginemaine.com/Lovewells_Fight.html (“1724 Attack at Old Dunstable”)

The victims of that one are buried in Nashua, NH at the “Old North Burial Grounds” which is located in South Nashua today. (It was then the north end of Dunstable which stretched on both sides of today’s NH/MA border.)

The mass grave with Lund & 7 others is seen here:

http://picasaweb.google.com/bchabot/OldNorthBurialGrounds#5318794679366866050

Thanks for stopping by Brian, and for contributing more to the story. Great shots at the burial ground by the way. I’ll have to head over there for a look around, I’m in Hudson.

I chronicled the creation of Old Dunstable here with a map showing the old boundaries http://wp.me/pCdVI-8i .

Be well