Marker Text:

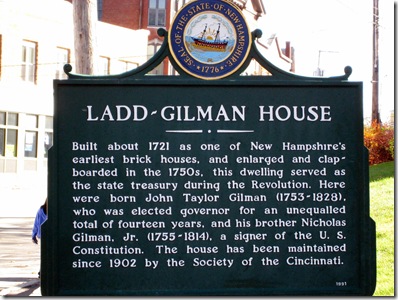

Built about 1721 as one of New Hampshire’s earliest brick houses, and enlarged and clapboarded in the 1750s, this dwelling served as the state treasury during the Revolution. Here were born John Taylor Gilman (1753-1828), who was elected governor for an unequalled total of fourteen years, and his brother Nicholas Gilman, Jr. (1755-1814), a signer of the U.S. Constitution. The house has been maintained since 1902 by the Society of the Cincinnati.

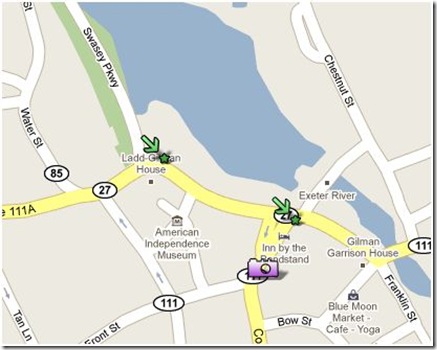

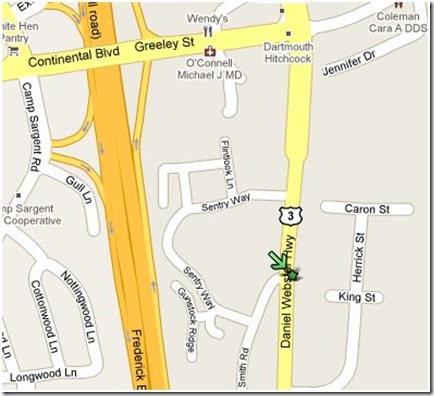

Located at the Ladd-Gilman house on Water St. in downtown Exeter, the Marker was erected in 1991. (Leftmost Placemark below)

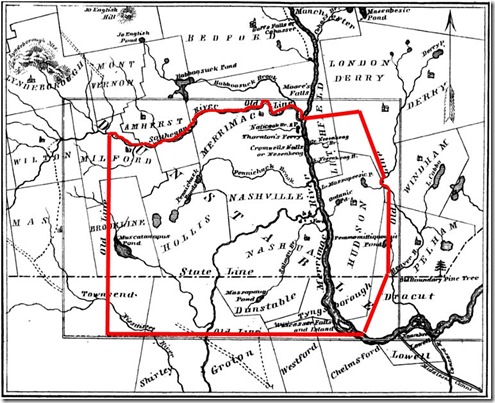

The Ladd-Gilman House gives us a chance to return to Exeter one more time before the Revolutionary War. This is a chance to catch up with Exeter’s history since the last marker from more than 80 years ago. After Rev. Wheelwright was booted out of town in 1642 and Exeter came under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, the town began to be settled in earnest.

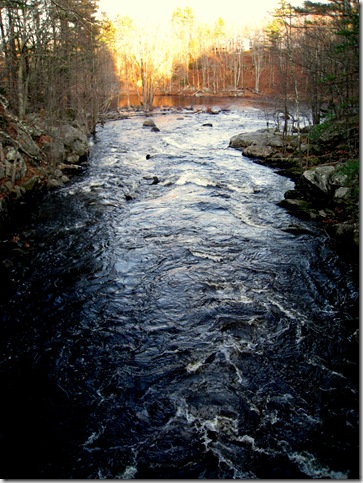

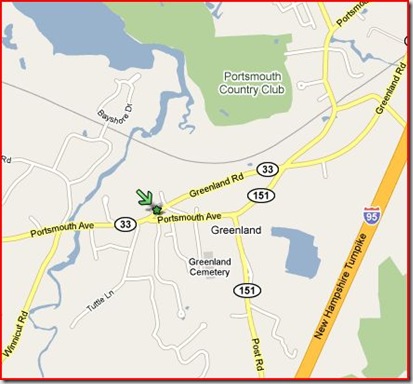

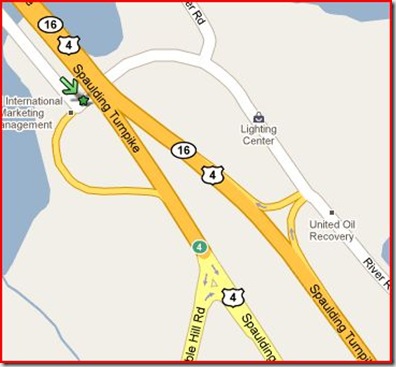

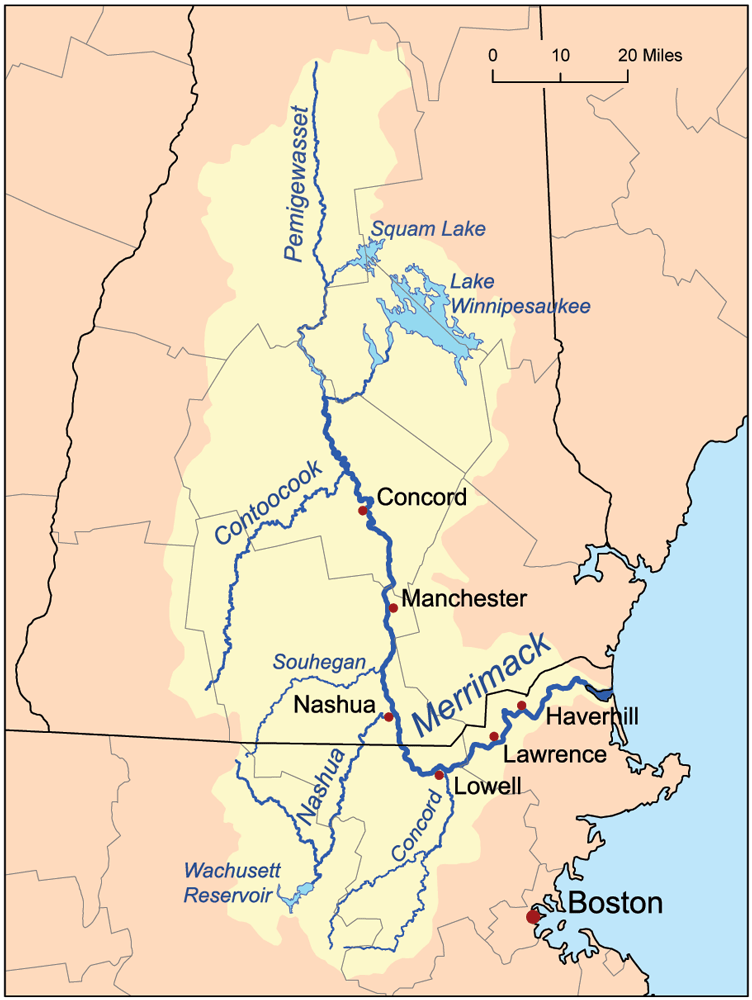

Exeter was a desirable place to settle for many reasons. As the Exeter river goes over the falls it becomes the Swampscott river and is part of Great Bay. Back then, before the construction of dams, salmon were plentiful as they headed from the ocean up the Exeter river to spawn. The Swampscott river, being a tidal river, provided access to Dover, Strawberry Banke and the ocean. Alewives were plentiful above the falls providing an opportunity to build fisheries and use the harvested fish to fertilize the soil as land was cleared and farms built. The first mill was erected on the east side of the river on the Exeter river falls (map above, center right). The homes of the settlers were generally on the west side of the river.

Exeter river to spawn. The Swampscott river, being a tidal river, provided access to Dover, Strawberry Banke and the ocean. Alewives were plentiful above the falls providing an opportunity to build fisheries and use the harvested fish to fertilize the soil as land was cleared and farms built. The first mill was erected on the east side of the river on the Exeter river falls (map above, center right). The homes of the settlers were generally on the west side of the river.

As with any new town representatives were selected, taxes set out for the common cause, plots of land claimed and bickered about, grumbles about Massachusetts Government and people generally being people. Into this new town being structured came a wealthy man named Edward Gilman:

… the settlement in Exeter of Edward Gilman in 1647, and his relatives shortly afterwards, men of property and energy, who set up saw-mills and gave an impulse to the business of the place. Bell, History of Exeter

The Gilman family prospered in Exeter as more of the family moved into the town. Over the next 50 years Exeter would grow steadily, the primary exports being ship masts, barrel staves and other products produced at the mills. The first garrison house would be built by a Gilman and still stands today at 12 Water Street (map above, lower right).

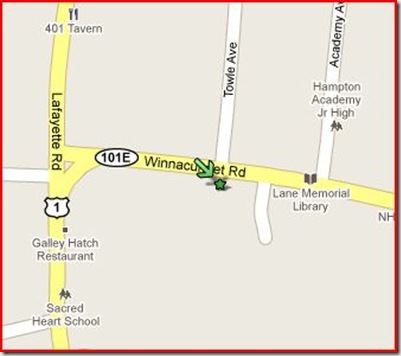

Nathaniel Ladd was born in Haverhill MA in the 1650s, married Elizabeth Gilman and eventually settled in Exeter. He managed to get into a bit of trouble in 1683 when he took part in Gove’s rebellion. Many were angry at provincial Governor who had dissolved the assemblies elected by the people to appoint his own guys. Ladd and 11 others (probably fortified with spirits) rode from Exeter to Hampton with guns and sword at the ready. They were all arrested except Ladd who managed to escape and went into hiding for a while. Nathaniel Ladd would meet an early death participating in a raid on the Indian settlement at Casco Bay in 1691. His eldest son, Nathaniel II would build what is today the Ladd-Gilman House.

The original house is all brick, but was clapboarded over later when additions were added in the 1750s. Through marriage between the Ladd and Gilman families in the 1700s the house was eventually owned by the Gilmans. Today the house is part of the American Independence Museum in Exeter, and displays historic documents including original drafts of the Declaration of Independence. Also on the museum property is the Folsom Tavern (pictured above), built in 1775 on the corner of today’s Front and Water streets. It was moved to this location in 2004. And before you ask, yes, George Washington visited here in 1783.

The original house is all brick, but was clapboarded over later when additions were added in the 1750s. Through marriage between the Ladd and Gilman families in the 1700s the house was eventually owned by the Gilmans. Today the house is part of the American Independence Museum in Exeter, and displays historic documents including original drafts of the Declaration of Independence. Also on the museum property is the Folsom Tavern (pictured above), built in 1775 on the corner of today’s Front and Water streets. It was moved to this location in 2004. And before you ask, yes, George Washington visited here in 1783.

There will be a little more on this important building in posts about the revolution.

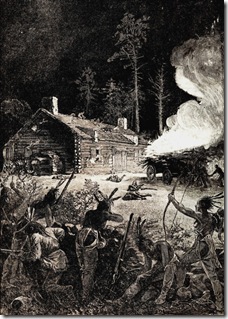

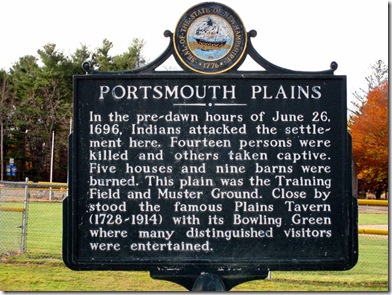

vulnerable to attack on the frontier.

vulnerable to attack on the frontier.

keep up or die. They travelled for 15 days all told, and as was the custom of the Indians at the time the captives were split between the participating Tribes.

keep up or die. They travelled for 15 days all told, and as was the custom of the Indians at the time the captives were split between the participating Tribes.

belonging to two persons named Chesley; killed two men in a canoe, and carried away two captives ; both of whom soon after made their escape.

belonging to two persons named Chesley; killed two men in a canoe, and carried away two captives ; both of whom soon after made their escape.