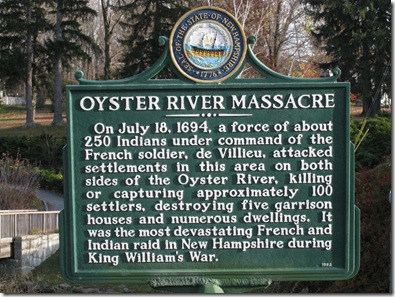

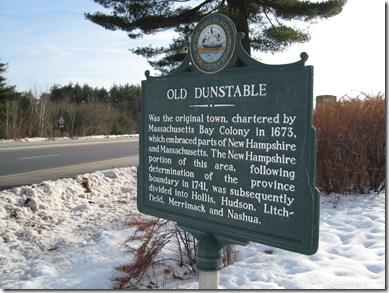

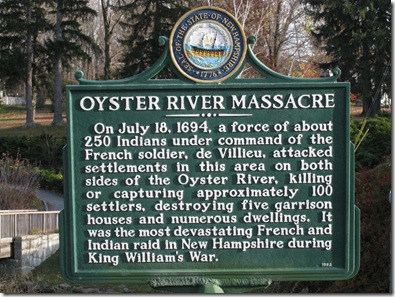

Marker Text:

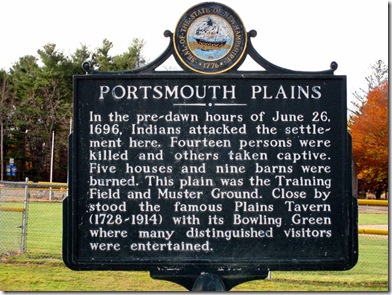

On July 18, 1694, a force of about 250 Indians under command of the French soldier, de Villieu, attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid in New Hampshire during King William’s war.

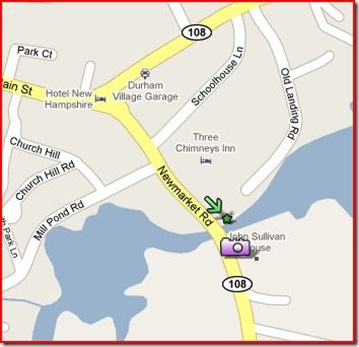

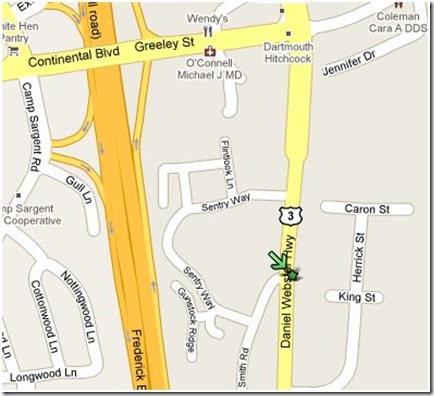

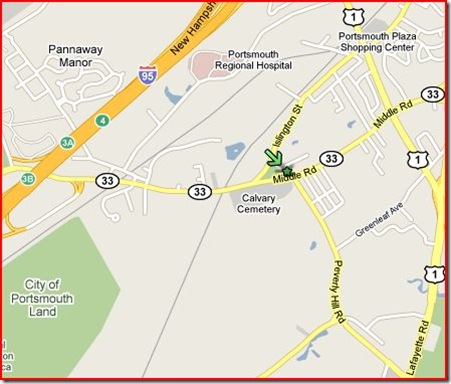

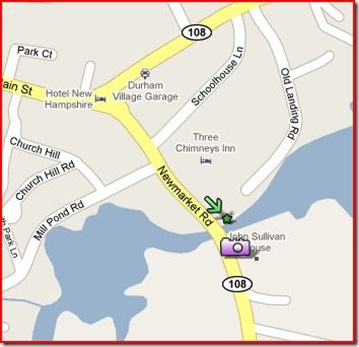

This marker is located on the south side of US 4, just east of its intersection with NH 108, just before the bridge over the Oyster River. Marker #89 “Major General John Sullivan” is just across the bridge to the south.

No Indians the day I visited.

No Indians the day I visited.

The Oyster River Massacre of 1694 wasn’t the first run in with the Abenaki, but it was the first organized by the French. The trouble really began in 1675 when the Plymouth Colony went to war with the local Wampanoag Indians in King Philip’s War.

Word of the war down south spread quickly among the Native American tribes and among the settlers all over New England. Up the coast of Maine at the Kennebeck River, the settlers looked for promises from the local Indians. They requested that they surrender their Muskets. It didn’t go so well. They began to attack remote settlements that were lightly guarded in Maine, and soon began doing the same in New Hampshire.

Belknap tells the tale, emphasis is mine:

…and having dispersed themselves into many small parties, that they might be the more extensively mischievous, in the month of September, they approached the plantations at Pascataqua, and made their first onset at Oyster river, then a part of the town of Dover, but now Durham. Here, they burned two houses  belonging to two persons named Chesley; killed two men in a canoe, and carried away two captives ; both of whom soon after made their escape. About the same time, a party of four laid in ambush near the road between Exeter and Hampton, where they killed one, and took another, who made his escape.

belonging to two persons named Chesley; killed two men in a canoe, and carried away two captives ; both of whom soon after made their escape. About the same time, a party of four laid in ambush near the road between Exeter and Hampton, where they killed one, and took another, who made his escape.

Within a few days an assault was made on the house of one Tozer at Newichwannock [today’s Salmon Falls River –Mike], wherein were fifteen women and children, all of whom, except two, were saved by the intrepidity of a girl of eighteen. She first seeing the Indians as they advanced to the house, shut the door and stood against it, till the others escaped to the next house, which was better secured. The Indians chopped the door to pieces with their hatchets, and then entering, they knocked her down, and leaving her for dead, went in pursuit of the others, of whom two children, who could not get over the fence, fell into their hands. The adventurous heroine recovered, and was perfectly healed of her wound.

The two following days, they made several appearances on both sides of the river, using much insolence, and burning two houses and three barns, with a large quantity of grain. Some shot were exchanged without effect, and a pursuit was made after them into the woods by eight men, but night obliged them to return without success. Five or six houses were burned at Oyster river, and two more men killed.

These daily insults could not be borne without indignation and reprisal. About twenty young men, chiefly of Dover, obtained leave of Major Waldron, then commander of the militia, to try their skill and courage with the Indians in their own way. Having scattered themselves in the woods, a small party of them discovered five Indians in a field near a deserted house, some of whom were gathering corn, and others kindling a fire to roast it. The men were at such a distance from their fellows that they could make no signal to them without danger of a discovery; two of them, therefore, crept along silently, near to the house, from whence they suddenly rushed upon those two Indians, who were busy at the fire, and knocked them down with the butts of their guns; the other three took the alarm and escaped.

Belknap, pp 72-73

The confrontation would continue in Maine and New Hampshire until 1678, when a treaty was signed at Casco Bay in today’s Portland, ME.

The Massacre of 1694

With the onset of King Williams War the French began to to enlist Indians to do their fighting for them. The French were mostly traders and had few major settlements and a lack of people. The Indians would be their militia in this war. The English settlers had signed an agreement with the local tribes to end hostilities in the Treaty of Pemaquid, and the French weren’t too happy.

Villebon, the French Governor of Acadia assigned de Vellieu and the “Fighting Priest” Thury to coordinate the attacks on the English colonies.

As usual, Dr. Belknap has the details. It’s long, but interesting! All highlights are mine:

The towns of Dover and Exeter being more exposed than Portsmouth or Hampton, suffered the greatest share in the common calamity.

The engagements made by the Indians in the treaty of Pemaquid, might have been performed if they had been left to their own choice. But the French missionaries had been for some years very assiduous in propagating their tenets among them, one of which was ‘ that to break faith with heretics was no sin.’ The Sieur de Villieu, who had distinguished himself in the defence of Quebec when Phips was before it, and had contracted a strong antipathy to the New-Englanders, being then in command at Penobscot, he with M. Thury, the missionary, diverted Madokawando and the other Sachems from complying with their engagements; so that pretences were found for detaining the English captives, who were more in number, and of more consequence than the hostages whom the Indians had given.

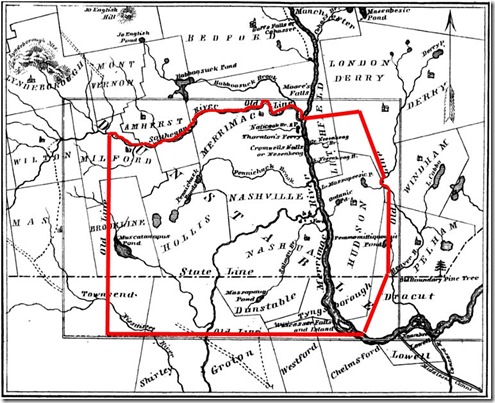

The settlement at Oyster river, within the town of Dover, was pitched upon as the most likely place; and it is said that the design of surprising it was publicly talked of at Quebec two months before it was put in execution.

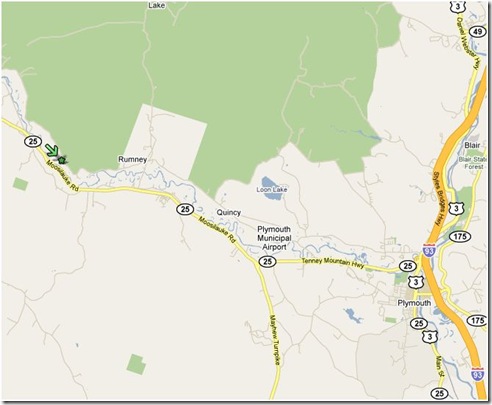

Rumors of Indians lurking in the woods thereabout made some of the people apprehend danger; but no mischief being attempted, they imagined them to be hunting parties, and returned to their security. At length, the necessary preparations being made, Villieu, with a body of two hundred and fifty Indians, collected from the tribes of St. John, Penobscot and Norridgewog, attended by a French Priest, marched for the devoted place.

…

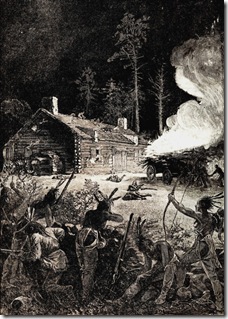

The enemy approached the place undiscovered, and halted near the falls on Tuesday evening, the seventeenth of July. Here they formed two divisions, one of which was to go on each side of the river and plant themselves in ambush, in small parties, near every house, so as to be ready for the attack at the rising of the sun; and the first gun was to be the signal.

John Dean, whose house stood by the saw-mill at the falls, intending to go from home very early, arose before the dawn of day, and was shot as he came out of his door. This firing, in part, disconcerted their plan; several parties who had some distance to go, had not then arrived at their stations; the people in general were immediately alarmed, some of them had time to make their escape, and others to prepare for their defence. The signal being given, the attack began in all parts where the enemy was ready.

Of the twelve garrisoned houses five were destroyed, viz. Adams’s, Drew’s, Edgerly’s Medar’s and Beard’s. They entered Adams’s without resistance, where they killed fourteen persons ; one of them, being a woman with child, they ripped open. The grave is still to be seen in which they were all buried. Drew surrendered his garrison on the promise of security, but was murdered when he fell into their hands. One of his children, a boy of nine years old, was made to run through a lane of Indians as a mark for them to throw their hatchets at, till they had dispatched him. Edgerly’s was evacuated. The people took to their boat, and one of them was mortally wounded before they got out of reach of the enemy’s shot. Beard’s and Medar’s were also evacuated and the people escaped.

The defenceless houses were nearly all set on fire, the inhabitants being either lulled or taken in them, or else in endeavoring to fly to the garrisons. Some escaped by hiding in the bushes and other secret places. Thomas Edgerly, by concealing himself in his cellar, preserved his house, though twice set on fire. The house of John Buss, the minister, was destroyed, with a valuable library. He was absent; his wife and family fled to the woods and escaped. The wife of John Dean, at whom the first gun was fired, was taken with her daughter, and carried about two miles up the river, where they were left under the care of an old Indian, while the others returned to their bloody work. The Indian complained of a pain in his head, and asked the woman what would be a proper remedy : she answered, occapee, which is the Indian word for rum, of which she knew he had taken a bottle from her house. The remedy being agreeable, he took a large dose and fell asleep ; and she took that opportunity to make her escape, with her child, into the woods, and kept herself concealed till they were gone.

The other seven garrisons, viz. Burnham’s, Bickford’s, Smith’s, Bunker’s, Davis’s, Jones’s and Woodman’s were resolutely and successfully defended. At Burnham’s, the gate was left open : The Indians, ten in number, who were appointed to surprise it, were asleep under the bank of the river, at the time that the alarm was given. A man within, who had been kept awake by the toothache, hearing the first gun, roused the people and secured the gate, just as the Indians, who were awakened by the same noise, were entering. Finding themselves disappointed, they ran to Pitman’s defenceless house, and forced the door at the moment, that he had burst a way through that end of the house which was next to the garrison, to which he with his family, taking advantage of the shade of some trees, it being moonlight, happily escaped.

Still defeated, they attacked the house of John Davis, which after some resistance, he surrendered on terms; but the terms were violated, and the whole family was either killed or made captives. Thomas Bickford preserved his house in a singular manner. It was situated near the river, and surrounded with a palisade. Being alarmed before the enemy had reached the house, he sent off his family in a boat, and then shutting his gate, betook himself alone to the defence of his fortress. Despising alike the promises and threats by which the Indians would have persuaded him to surrender, he kept up a constant fire at them, changing his dress as often as he could, shewing himself with a different cap, hat or coat, and sometimes without either, and giving directions aloud as if he had a number of men with him. Finding their attempt vain, the enemy withdrew, and left him sole master of the house, which he had defended with such admirable address.

Smith’s, Bunker’s and Davis’s garrisons, being seasonably apprised of the danger, were resolutely defended. One Indian was supposed to be killed and another wounded by a shot from Davis’s. Jones’s garrison was beset before day; Captain Jones hearing his dogs bark, and imagining wolves might be near, went out to secure some swine and returned unmolested. He then went up into the flankart and sat on the wall. Discerning the flash of a gun, he dropped backward; the ball entered the place from whence he had withdrawn his legs. The enemy from behind a rock kept firing on the house for some time, and then quitted it. During these transactions, the French priest took possession of the meeting-house, and employed himself in writing on the pulpit with chalk; but the house received no damage.

Those parties of the enemy who were on the south side of the river having completed their destructive work, collected in a field adjoining to Burnham’s garrison, where they insultingly showed their prisoners, and derided the people, thinking themselves out of reach of their shot. A young man from the sentry-box fired at one who was making some indecent signs of defiance, and wounded him in the heel: Him they placed on a horse and carried away. Both divisions then met at the falls, where they had parted the evening before, and proceeded together to Capt. Woodman’s garrison. The ground being uneven, they approached without danger, and from behind a hill kept up a long and severe fire at the hats and caps which the people within held up on sticks above the walls, without any other damage than galling the roof of the house.

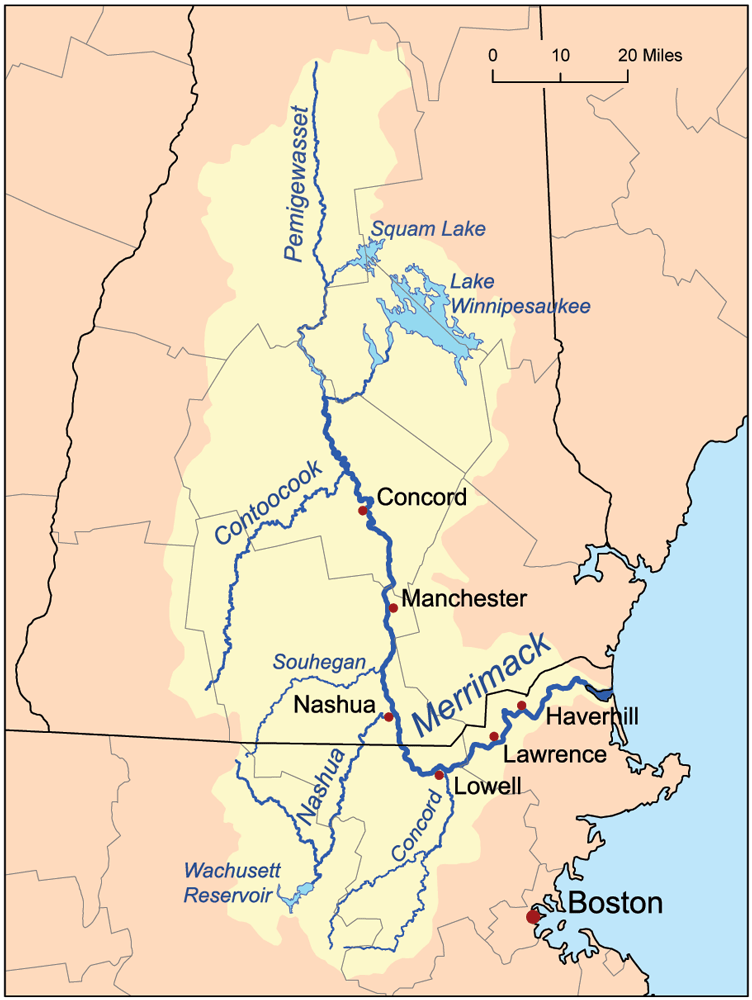

At length, apprehending it was time for the people in the neighboring settlements to be collected in pursuit of them, they finally withdrew; having killed and captivated between ninety and an hundred persons, and burned about twenty houses, of which five were garrisons. The main body of them retreated over Winnipiseogee lake, where they divided their prisoners…

Belknap pp137-141

At dawn on leap day, February 29th 1704, the settlement at Deerfield came under attack from a force of 300-400 Indians and their French commanders. Two Garrisons protected the town, one surrounded by a high palisade. Fearing attacks, many residents spent their nights within the garrison walls. The attack force stealthily approached the town and climbed snow drifts to get inside the palisade and open the gates. The massacre was on. As dawn broke hatchets fell and guns fired. The Indians ransacked and burned homes lighting up the skies and alerting settlements to the south.

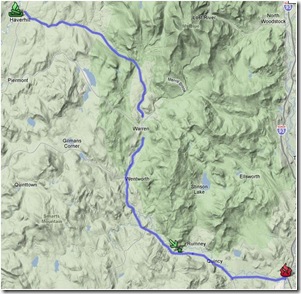

At dawn on leap day, February 29th 1704, the settlement at Deerfield came under attack from a force of 300-400 Indians and their French commanders. Two Garrisons protected the town, one surrounded by a high palisade. Fearing attacks, many residents spent their nights within the garrison walls. The attack force stealthily approached the town and climbed snow drifts to get inside the palisade and open the gates. The massacre was on. As dawn broke hatchets fell and guns fired. The Indians ransacked and burned homes lighting up the skies and alerting settlements to the south. The pattern would be the same as befell Hanah Dustin from Haverhill 7 years earlier: Strike at dawn, pillage, burn the town, take captives and escape north. The town garrisons and militia put up a valiant fight eventually driving off the attack. 48 were killed, 140 “alive at home” (wounded) and 112 people were taken captive.

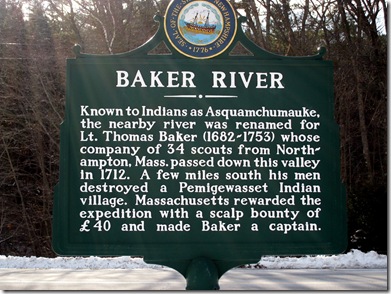

The pattern would be the same as befell Hanah Dustin from Haverhill 7 years earlier: Strike at dawn, pillage, burn the town, take captives and escape north. The town garrisons and militia put up a valiant fight eventually driving off the attack. 48 were killed, 140 “alive at home” (wounded) and 112 people were taken captive. Now we can get to the event that earned Thomas Baker his promotion to Captain, and the naming of a river after him. It’s not as exciting as the Deerfield massacre.

Now we can get to the event that earned Thomas Baker his promotion to Captain, and the naming of a river after him. It’s not as exciting as the Deerfield massacre.

George I ruled to his death in 1727, and was followed by his son, George II. This time New England wouldn’t be able to escape the continental spat. England went to war in 1740 in the

George I ruled to his death in 1727, and was followed by his son, George II. This time New England wouldn’t be able to escape the continental spat. England went to war in 1740 in the

common all over New Hampshire. Beyond the coast the early settlers were farmers. In the late 1700s and the 1800s most of the forests you see today in southern NH were farmland. That required clearing huge tracts of forests, building homesteads and outbuildings, digging up the rocks (lots of rocks) and planting the land. The wood from the trees was milled into lumber or ship masts and sold back to England or used to build here.

common all over New Hampshire. Beyond the coast the early settlers were farmers. In the late 1700s and the 1800s most of the forests you see today in southern NH were farmland. That required clearing huge tracts of forests, building homesteads and outbuildings, digging up the rocks (lots of rocks) and planting the land. The wood from the trees was milled into lumber or ship masts and sold back to England or used to build here.

vulnerable to attack on the frontier.

vulnerable to attack on the frontier.

keep up or die. They travelled for 15 days all told, and as was the custom of the Indians at the time the captives were split between the participating Tribes.

keep up or die. They travelled for 15 days all told, and as was the custom of the Indians at the time the captives were split between the participating Tribes.

belonging to two persons named Chesley; killed two men in a canoe, and carried away two captives ; both of whom soon after made their escape.

belonging to two persons named Chesley; killed two men in a canoe, and carried away two captives ; both of whom soon after made their escape.

.jpg)